The Battle of Five Armies. Well, it certainly was a battle, and the movie was mostly focused on fighting. I went to see the new (and last!) Hobbit movie a few days ago, and overall, I enjoyed it, and am sad that there will be no more Tolkien movies (or will there? Silmarillion anyone?). Martin Freeman was perfect as Bilbo, and when I reread the book, I pictured him as Bilbo. The other actors were great too, and even though there were many who weren't in the books, I liked how they had some "comebacks" of Lord of the Rings (LOTR) characters, like Galadriel, Legolas (Ya!), Elrond, Saruman, and Gandalf, but Elrond and Gandalf were legitimate because they were actually in the Hobbit.

The Battle of Five Armies. Well, it certainly was a battle, and the movie was mostly focused on fighting. I went to see the new (and last!) Hobbit movie a few days ago, and overall, I enjoyed it, and am sad that there will be no more Tolkien movies (or will there? Silmarillion anyone?). Martin Freeman was perfect as Bilbo, and when I reread the book, I pictured him as Bilbo. The other actors were great too, and even though there were many who weren't in the books, I liked how they had some "comebacks" of Lord of the Rings (LOTR) characters, like Galadriel, Legolas (Ya!), Elrond, Saruman, and Gandalf, but Elrond and Gandalf were legitimate because they were actually in the Hobbit.

The fighting, however, was overdone to the extreme. Although the battle was mentioned to be terrible and lasting a long time in the book, there wasn't much time actually spent on it in the book. Of course, the graphics were excellent, but it was way too much. I think it would have been better if the third movie started after Smaug destroyed Laketown, just so there wouldn't be two large battles (though the actual "Battle of Five Armies" was by far the most significant one. Or if it had started when the dwarves actually entered the mountain, and then they wouldn't have had to put so much time into the battles.

The fighting, however, was overdone to the extreme. Although the battle was mentioned to be terrible and lasting a long time in the book, there wasn't much time actually spent on it in the book. Of course, the graphics were excellent, but it was way too much. I think it would have been better if the third movie started after Smaug destroyed Laketown, just so there wouldn't be two large battles (though the actual "Battle of Five Armies" was by far the most significant one. Or if it had started when the dwarves actually entered the mountain, and then they wouldn't have had to put so much time into the battles.

Although the elves did not play much of a significant role in the book (at least, not personally, since they did come in an army to the mountain) I really liked how they introduced them as more major characters. Thranduil was an awesome character--not a good one, but it would have been a captivating movie if it were just about him. And Legolas was...well, you can't go wrong with putting Legolas in the movie. Though I did find that he was a bit too remote and cold compared to LOTR. Galadriel was also a good addition, especially the scene where she saves Gandalf and uses her powers to banish Sauron ("banish" in the sense of "delay him until LOTR starts") by going into her "creepy powerful" mode, for lack of a better word (if you've seen LOTR, you know what I mean). Although it was not as important as later scenes, that scene where she, Elrond, and Saruman came to rescue Gandalf and fight the Nazgul was one of my favourite parts (As I moved on in the movies, I grew used to them adding things in that weren't in the books, and actually liked it, because then there were things I didn't know about, so there was some surprise). In this scene, most of the members of the Grey Council came together to fight the forces of darkness, and it was really neat to see them all there being awesome. Galadriel was the main "star" in this scene, which I liked, since she's one of my favourite characters, though at the end, I didn't like it how Saruman and Elrond had to save her since she

Although the elves did not play much of a significant role in the book (at least, not personally, since they did come in an army to the mountain) I really liked how they introduced them as more major characters. Thranduil was an awesome character--not a good one, but it would have been a captivating movie if it were just about him. And Legolas was...well, you can't go wrong with putting Legolas in the movie. Though I did find that he was a bit too remote and cold compared to LOTR. Galadriel was also a good addition, especially the scene where she saves Gandalf and uses her powers to banish Sauron ("banish" in the sense of "delay him until LOTR starts") by going into her "creepy powerful" mode, for lack of a better word (if you've seen LOTR, you know what I mean). Although it was not as important as later scenes, that scene where she, Elrond, and Saruman came to rescue Gandalf and fight the Nazgul was one of my favourite parts (As I moved on in the movies, I grew used to them adding things in that weren't in the books, and actually liked it, because then there were things I didn't know about, so there was some surprise). In this scene, most of the members of the Grey Council came together to fight the forces of darkness, and it was really neat to see them all there being awesome. Galadriel was the main "star" in this scene, which I liked, since she's one of my favourite characters, though at the end, I didn't like it how Saruman and Elrond had to save her since she

had spent her powers. She went from being super powerful to completely powerless on the ground. I think she gave most of her strength to save Gandalf even without her banishing Sauron, so that was all right. And then Radagast comes in on his "bunny-mobile" (one of my favourite parts of the movie is these bunnies! Or rather, Rhosgobel rabbits) to take Gandalf away, so he gets to be part of the show too.

Another quite powerful scene, though this one was creepy, was when Thorin was fighting Azog on the ice and (spoiler alert) Azog falls in and there are a few moments when you see him under the ice, hoping he's dead but knowing that he couldn't really be, and he jumps out and kills Thorin. Well, Thorin kills him, but Thorin is mortally wounded.

Another quite powerful scene, though this one was creepy, was when Thorin was fighting Azog on the ice and (spoiler alert) Azog falls in and there are a few moments when you see him under the ice, hoping he's dead but knowing that he couldn't really be, and he jumps out and kills Thorin. Well, Thorin kills him, but Thorin is mortally wounded.

Another added character is the elf Tauriel. I have mixed feelings about Tauriel. First of all, in the previous movie, I thought "What's she doing here? She's not in the book! She's not even in LOTR!" (hence, that's why Galadriel, Legolas, Radagast, and co. are permissible). But of course, the point was to add a major female character, because literally, there are NO female characters in the Hobbit book. And they couldn't have had Galadriel running around killing orcs...well, they could have, but that just wouldn't fit. Anyhow, that was my only reservation, because I really liked Tauriel as a character. But of course, (spoiler alert for non-Hobbit readers), Kili dies, who she loves, so that's just more depressing. I secretly hoped Kili and Fili wouldn't die, but was prepared for it, because I knew Peter Jackson wouldn't lose the opportunity to kill off good characters when he had the book's backing. The whole love thing between Tauriel and Kili was sweet, and of course, it was with the dwarf who looked least "dwarfish" (except perhaps Thorin). I just wish Kili hadn't died, but even then, I don't think it could have worked out.

Another added character is the elf Tauriel. I have mixed feelings about Tauriel. First of all, in the previous movie, I thought "What's she doing here? She's not in the book! She's not even in LOTR!" (hence, that's why Galadriel, Legolas, Radagast, and co. are permissible). But of course, the point was to add a major female character, because literally, there are NO female characters in the Hobbit book. And they couldn't have had Galadriel running around killing orcs...well, they could have, but that just wouldn't fit. Anyhow, that was my only reservation, because I really liked Tauriel as a character. But of course, (spoiler alert for non-Hobbit readers), Kili dies, who she loves, so that's just more depressing. I secretly hoped Kili and Fili wouldn't die, but was prepared for it, because I knew Peter Jackson wouldn't lose the opportunity to kill off good characters when he had the book's backing. The whole love thing between Tauriel and Kili was sweet, and of course, it was with the dwarf who looked least "dwarfish" (except perhaps Thorin). I just wish Kili hadn't died, but even then, I don't think it could have worked out.

The last thing I wanted to mention was Thorin. Having recently reread the book, I realized that they made Thorin way too solemn and brooding compared to the book (they also did this with Beorn). They did a good job in this movie portraying Thorin's "dragon sickness" (gold obsession), and he acted this part really well.

So if you can put up with the fighting, this is a great movie. I think it would be awesome if Peter Jackson did more movies, even if they weren't Tolkien's actual stories, but something like a mini-series about individual characters, like their backstory, or a sort of "in the meantime, while Bilbo and co. were on their adventure...". They did a bit of that with Gandalf and the elves in the Hobbit trilogy, but more would be neat too.

Aizai the Forgotten is included in a Young Adult Fantasy e-book bundle for only $1.99! Check it out while it's still at this super low price:

http://www.amazon.com/Captivating-Tales-Tween-YA-Bundle-ebook/dp/B00PR810K4/ref=sr_1_63?s=digital-text&ie=UTF8&qid=1417721539&sr=1-63

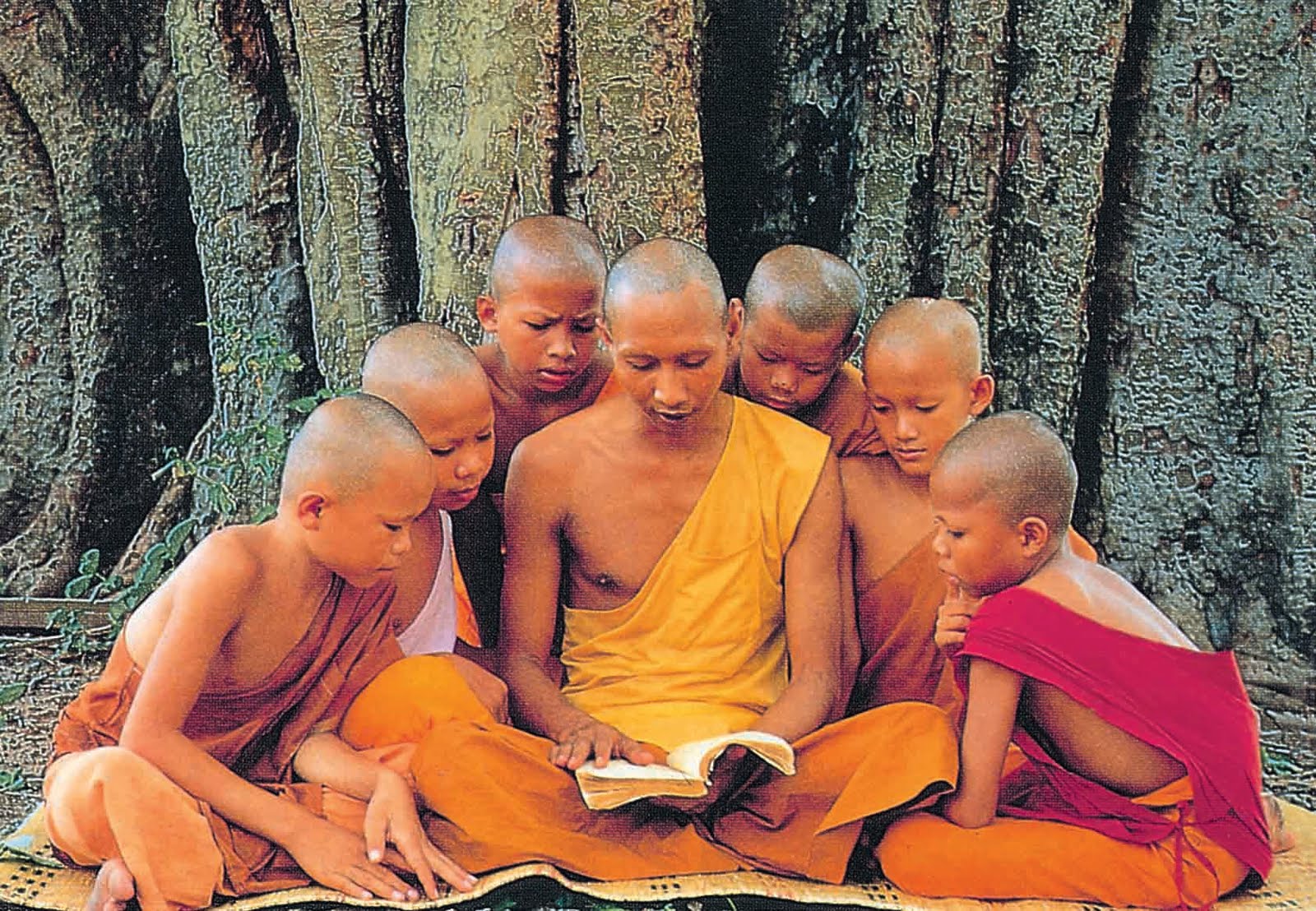

I've recently read The Dhammapada, a collections of sayings from the Buddha. It's a beautiful little book that you can read bits of when you like (though I read it from cover to cover). So here is the quote for today:

From The Dhammapada, (ancient Buddhist text)

"Your worst enemy cannot harm you

As much as your own thoughts, unguarded.

But once mastered,

No one can help you as much,

Not even your own father or your mother.

You are the source

Of all purity and impurity.

No one purifies another."

From this, we can see that the main contributor to your well-being is yourself, in particular, the state of mind from which your thoughts arise and form your perceptions of others and the world. So in order to help others, which is one of the goals of Buddhists, you must help yourself. Not by making yourself wealthy, but by cultivating your thoughts and intentions to good purposes.

Others can teach you and guide you to the right path, but only you can walk it yourself. So by cultivating yourself, spiritually in particular, you will be better able to guide others to do the same, and allow them to purify themselves with the knowledge you possess from your own experiences. Although Buddhists focus on helping people achieve happiness and virtue, the ultimate goal is to attain liberation from the world and to achieve the state of Nirvana, and in particular, to help every sentient being in the world get there. This is not attainable through things like sacrifices but by purifying one's mind. As the quote says, the worst enemies to this goal, the ultimate goal, are your own thoughts. We all know that negative thoughts can have large impacts on ourselves, from what we believe, to our outlook on the world, to our actions that flow from them. We must really master ourselves as opposed to others: ultimately, it is not a war against whatever villain might be impeding our success, but the fear and hatred that is in ourselves, because that is what we can never escape from, even though we might be in a place that is safe from all physical dangers. Yes, we have to be free from those "villains" too, but once free of them, will we be able to survive with ourselves? (This isn't really in the Dhammapada. Shakespeare's Macbeth is an extreme example of what I'm thinking about). For who really is your worst enemy? We can be our own worst enemies, and so too our own saviours.

Others can teach you and guide you to the right path, but only you can walk it yourself. So by cultivating yourself, spiritually in particular, you will be better able to guide others to do the same, and allow them to purify themselves with the knowledge you possess from your own experiences. Although Buddhists focus on helping people achieve happiness and virtue, the ultimate goal is to attain liberation from the world and to achieve the state of Nirvana, and in particular, to help every sentient being in the world get there. This is not attainable through things like sacrifices but by purifying one's mind. As the quote says, the worst enemies to this goal, the ultimate goal, are your own thoughts. We all know that negative thoughts can have large impacts on ourselves, from what we believe, to our outlook on the world, to our actions that flow from them. We must really master ourselves as opposed to others: ultimately, it is not a war against whatever villain might be impeding our success, but the fear and hatred that is in ourselves, because that is what we can never escape from, even though we might be in a place that is safe from all physical dangers. Yes, we have to be free from those "villains" too, but once free of them, will we be able to survive with ourselves? (This isn't really in the Dhammapada. Shakespeare's Macbeth is an extreme example of what I'm thinking about). For who really is your worst enemy? We can be our own worst enemies, and so too our own saviours.

The path that Buddhists follow to master themselves is called the Eightfold Path, which has eight qualities to cultivate in order to awaken to your true nature, and to eliminate the negative qualities that might be obscuring it:

Tweet

Today's post is about reincarnation in Hinduism, though much of this is in common with Buddhism as well.

This quote is from the Bhagavad Gita, when Krishna, the avatar of the god Vishnu, is speaking to a warrior called Arjuna to try to get him to do his duty to fight in a war (see picture-->).

From The Bhagavad Gita (ancient Hindu text):

"The Spirit is neither born nor does it die at any time. It does not come into being, or cease to exist. It is unborn, eternal, permanent, and primeval. The Spirit is not destroyed when the body is destroyed... Just as a person puts on new garments after discarding the old ones; similarly, the living entity or the individual soul acquires new bodies after casting away the old bodies."

The soul is called atman in Sanskrit, which is what Krishna is speaking about: it is eternal, and although we change as humans when we are in a physical body, the soul itself does not change. It is currently embodied because of its ignorance of the higher spiritual reality, by mistaking itself for the body it is currently inhabiting, and this causes it to undergo reincarnation until it can gain an understanding of the truth.

The cycle of reincarnation is called samsara, which is ruled by karma. Karma, as most people know, is the result of our good or bad actions, and causes the person to be born into their next life in a body and place in accordance with what they have earned through karma. It may seem strange that the soul would accumulate affects from the body it inhabits when it is an imperishable substance. This is explained by the concept of two different bodies: the "subtle body" and the "gross body".

The cycle of reincarnation is called samsara, which is ruled by karma. Karma, as most people know, is the result of our good or bad actions, and causes the person to be born into their next life in a body and place in accordance with what they have earned through karma. It may seem strange that the soul would accumulate affects from the body it inhabits when it is an imperishable substance. This is explained by the concept of two different bodies: the "subtle body" and the "gross body".

The subtle body is the vehicle for the atman to pass between lives. It contains our consciousness, intelligence, ego, and other mental properties. The gross body is just the physical body with all its senses. The subtle body is the link between the soul and the gross body, so that every action we perform (via the gross body) leaves an imprint on the subtle body. The soul will eventually have to experience the results of the actions imprinted in the subtle body. So even though the gross body is destroyed at death, the effects of its actions have been left of the subtle body, causing the soul to be incarnated again to experience these effects. It seems then, that by the very nature of actions, we cannot experience all of their affects in our present life, which is an interesting thought.

The goal, however, is to escape this cycle and achieve spiritual liberation, called moksha. It's basically the same thing as nirvana in Buddhism. To attain moksha, one must abandon their desires and gain knowledge of their true nature. It is to free oneself from accumulating karma, both good and bad karma, because somehow, karma is what binds us to bodies. It makes it so that we are reborn again and again, which might not sound like a bad thing (if we're good), but beyond the cycle of samsara is a state of perfection where there is no suffering. Karma is based on actions, and we are meant to experience all the consequences ("fruits", it is called) of our actions by a certain kind of cause and effect, but Hindus also say that we cannot experience all the effects of our actions in our present life, which necessitates that we are born again so we can experience them. So we can only get out of the cycle by becoming detached to the fruits of our actions and freeing ourselves from desire, so making it so that we do not accumulate karma, since the point of reincarnation is to experience the fruits of our karma. This rests on realizing the true nature of ourselves, which is our soul, atman. At this point, all the lessons from our previous lives have been learned and all karma has been fulfilled, so there is no longer a need to return again.

This is similar to other spiritual traditions, where someone must gain truth about a higher reality (beyond the world they live in) and their own nature in order to escape from the burdens of the world to go to a realm of peace. It's interesting just how many different religions and philosophies have similar ideas about reincarnation, which might not be a coincidence. There are also many accounts of people who are connected to past lives, something sort of like a fluke, since we're not "supposed to" remember previous lives. You can read about how this relates to science in a neat book called The Soul Genome.

See what me and other Muse it Up authors say about the process of writing novels:

http://museituppublishing.blogspot.ca/2014/09/sunday-musings-september-21-2014.html

Science is philosophy, I'd like to argue. The original term for science, "natural philosophy", was much more apt to describe what it is. But what is "natural philosophy"?

Natural philosophy never really "started", for the natural desire for humans to inquire and understand the world is intrinsic to our nature, and so in a sense we have always been natural philosophers. Aristotle, however, contributed greatly to our understanding of nature through his observations and philosophy. To Aristotle, natural philosophy was concerned with analyzing the causes behind natural phenomena, such as: why does the sun rise each day? Why does a plant grow from a seed?

Natural philosophy never really "started", for the natural desire for humans to inquire and understand the world is intrinsic to our nature, and so in a sense we have always been natural philosophers. Aristotle, however, contributed greatly to our understanding of nature through his observations and philosophy. To Aristotle, natural philosophy was concerned with analyzing the causes behind natural phenomena, such as: why does the sun rise each day? Why does a plant grow from a seed?

In the Medieval world, Aristotle's work was rediscovered in Europe from where it was preserved by the Islamic world, and it was incorporated into Medieval theology. Natural philosophy and theology became the vehicles to understand the world, and together, they were used to describe the world in terms of purposes and connections to higher powers. Everyone learned Aristotelian philosophy, and Aristotelian scholasticism dominated natural philosophy, and indeed, became synonymous with it, until late in the seventeenth century.

During the seventeenth century, natural philosophy was transformed by the Scientific Revolution. Advances in mathematics, experimentation, and technology greatly changed the Medieval worldview. The natural philosophy of the 17th century started to resemble what we now call "science", and was largely spurred by Descartes and Francis Bacon. They focused on extracting truth about nature by theoretical (mathematics and logic) and experimental (observations, telescopes, etc.) means in order to describe a mechanical universe without direct divine intervention. However, they certainly had their own theologies incorporated into their philosophies, though these usually were not theological explanations for natural phenomena.

Natural philosophy continued its spurt of development up to the present (and, of course, it's still going on), evolving our picture of the universe by the works of people such as Newton, Copernicus, Galileo, Darwin, Faraday, Einstein, Bohr, etc.

Although the conception of natural philosophers has changed over the course of the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and especially in the seventeenth century, the pursuit of knowledge about the physical world was not separate to philosophy, but was indeed a kind of philosophy. Natural philosophy was not so strictly classified into disciplines like Genetics, Neuroscience, or Mathematics (many of which our nineteenth century predecessors labelled), but all disciplines were seen in a more united sense than they are now. There is certainly overlap now, but the general division seen in schools does not help to portray the underlying unity between the areas of science. And indeed, it does nothing to show the unity of science with philosophy, both of which might as well be living on different planets. But philosophy is a study of the fundamental nature of the world, of knowledge, and of all of reality. Above all, it is a method of inquiry, of using rational thinking to come to a better understanding of one's self and the world. It is a love of wisdom, as its name in Greek implies. Where science fits into this is that science is a kind of philosophy, namely the philosophy of the natural world, as opposed to ethics or logic (though logic is obviously used as a tool in science).

You can read another article about this topic here.

Tweet

I recently finished a book about the philosophy of the Druids, the best one I've read so far, and this quote is about one of the ideas the Druids had that is in common with many other ancient religions and philosophies.

I recently finished a book about the philosophy of the Druids, the best one I've read so far, and this quote is about one of the ideas the Druids had that is in common with many other ancient religions and philosophies.

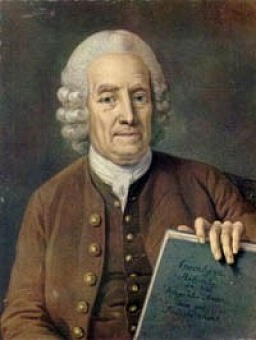

From Sir John Daniel's The Philosophy of Ancient Britain (1926):

"The Science of Correspondences is therefore the science by which we perceive principles operating in the spiritual world, and by which we trace those same principles in the order of their progression into their types in nature, and thus prove by strict analysis the truth of our perception. It unfolds the correspondence between things spiritual and natural, between every object in the spiritual world, between God and His Church, and between the spirit and the letter of His Word."

The Science of Correspondences (SOC, I'll call it for short), was first written about by Emanuel Swedenborg, though it was known to the ancients, such as the Druids, centuries before. The basic idea is that everything in the world, from plants to humans to stars and galaxies, corresponds to higher spiritual principles. This gives them their order, the laws by which they unfold. It's sort of the same idea as Plato's forms, the eternal, unchanging concepts that things in the physical world partake in, like a plant participating in the perfect form of "plantness", though it is never as perfect as the spiritual form.

Just about all of the Bible was written by means of correspondences, such as, as Swedenborg pointed out, the sacrifices, offerings, clothing, and all those little details about buildings and things that don't seem important, though convey a secret formula that can be read by people who understand the encoded SOC.

The SOC can aide us in understanding the foundations of our scientific knowledge as well, as John Daniel points out, saying that the scientist, "having done his utmost...to reach a solution to the riddle of the universe...is faced with a hiatus he cannot bridge, an infinity he cannot fathom." This sounds similar to what is facing physics right now (even though this was written in the 1920s), with the attempts of particle physicists to probe deeper and deeper into the nature of matter and the structure of the universe. The SOC can aide us in understanding the uses of things and their cause and effect. This is not to put a divine purpose into every little thing in the world, but to see greater patterns in the evolution of the world and the universe at large. It is "the Science of Sciences", what I think is a more metaphysical kind of philosophy of science. It connects the workings of the world with more basic principles, and as John Daniel says, "as the natural world is one of the effects whose causes are in the spiritual world, and whose ends are in the Divine, it is impossible to understand the meaning of one link without having regard to the complete chain."

I think it is important to have more philosophy in sciences, especially physics dealing with the very small and very large, and the SOC is certainly a way to do this. Whether it will be able to 'bridge our hiatus', I don't know, but by uniting the spiritual aspect of the world with the physical (a very Aizian idea, if you've read my novel Aizai the Forgotten), we can certainly gain a better understanding of the universe. Especially with physics theories about the multiverse, extra dimensions, the universe as being a mathematical structure, and other such things, what if what they were describing is a fuller spiritual world? This could correspond to philosophies such as Kabbalism or Neoplatonism. For example, in Neoplatonism, each level of existence, "hypostases", is a reflection (or dispersion would be more fitting) of the one above it, and so the lower worlds are a reflection of the higher, creating a link between them. And so we see the well-known phrase again: "As above, so below".

I think it is important to have more philosophy in sciences, especially physics dealing with the very small and very large, and the SOC is certainly a way to do this. Whether it will be able to 'bridge our hiatus', I don't know, but by uniting the spiritual aspect of the world with the physical (a very Aizian idea, if you've read my novel Aizai the Forgotten), we can certainly gain a better understanding of the universe. Especially with physics theories about the multiverse, extra dimensions, the universe as being a mathematical structure, and other such things, what if what they were describing is a fuller spiritual world? This could correspond to philosophies such as Kabbalism or Neoplatonism. For example, in Neoplatonism, each level of existence, "hypostases", is a reflection (or dispersion would be more fitting) of the one above it, and so the lower worlds are a reflection of the higher, creating a link between them. And so we see the well-known phrase again: "As above, so below".

If our physical world is derived from a higher spiritual world, we will indeed reach a limit in our understanding of the physical universe as John Daniel pointed out, even if there are higher physical dimensions and other worlds, because the laws that govern our world derive from laws that encompass a higher level of reality. So we have to go a step above, and science, since it deals with understanding the physical world, can't get there without something else. Mathematics might well connect our world to others, and we can already see this with string theory, higher dimensions, and other such theories.

It seems like the ancients, with their SOC, knew something which we would do well to uncover if we actually want to understand the universe we live in, and to understand ourselves.