Today's post is about reincarnation in Hinduism, though much of this is in common with Buddhism as well.

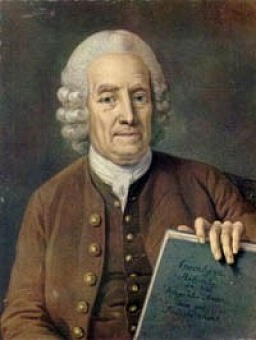

This quote is from the Bhagavad Gita, when Krishna, the avatar of the god Vishnu, is speaking to a warrior called Arjuna to try to get him to do his duty to fight in a war (see picture-->).

From The Bhagavad Gita (ancient Hindu text):

"The Spirit is neither born nor does it die at any time. It does not come into being, or cease to exist. It is unborn, eternal, permanent, and primeval. The Spirit is not destroyed when the body is destroyed... Just as a person puts on new garments after discarding the old ones; similarly, the living entity or the individual soul acquires new bodies after casting away the old bodies."

The soul is called atman in Sanskrit, which is what Krishna is speaking about: it is eternal, and although we change as humans when we are in a physical body, the soul itself does not change. It is currently embodied because of its ignorance of the higher spiritual reality, by mistaking itself for the body it is currently inhabiting, and this causes it to undergo reincarnation until it can gain an understanding of the truth.

The cycle of reincarnation is called samsara, which is ruled by karma. Karma, as most people know, is the result of our good or bad actions, and causes the person to be born into their next life in a body and place in accordance with what they have earned through karma. It may seem strange that the soul would accumulate affects from the body it inhabits when it is an imperishable substance. This is explained by the concept of two different bodies: the "subtle body" and the "gross body".

The cycle of reincarnation is called samsara, which is ruled by karma. Karma, as most people know, is the result of our good or bad actions, and causes the person to be born into their next life in a body and place in accordance with what they have earned through karma. It may seem strange that the soul would accumulate affects from the body it inhabits when it is an imperishable substance. This is explained by the concept of two different bodies: the "subtle body" and the "gross body".

The subtle body is the vehicle for the atman to pass between lives. It contains our consciousness, intelligence, ego, and other mental properties. The gross body is just the physical body with all its senses. The subtle body is the link between the soul and the gross body, so that every action we perform (via the gross body) leaves an imprint on the subtle body. The soul will eventually have to experience the results of the actions imprinted in the subtle body. So even though the gross body is destroyed at death, the effects of its actions have been left of the subtle body, causing the soul to be incarnated again to experience these effects. It seems then, that by the very nature of actions, we cannot experience all of their affects in our present life, which is an interesting thought.

The goal, however, is to escape this cycle and achieve spiritual liberation, called moksha. It's basically the same thing as nirvana in Buddhism. To attain moksha, one must abandon their desires and gain knowledge of their true nature. It is to free oneself from accumulating karma, both good and bad karma, because somehow, karma is what binds us to bodies. It makes it so that we are reborn again and again, which might not sound like a bad thing (if we're good), but beyond the cycle of samsara is a state of perfection where there is no suffering. Karma is based on actions, and we are meant to experience all the consequences ("fruits", it is called) of our actions by a certain kind of cause and effect, but Hindus also say that we cannot experience all the effects of our actions in our present life, which necessitates that we are born again so we can experience them. So we can only get out of the cycle by becoming detached to the fruits of our actions and freeing ourselves from desire, so making it so that we do not accumulate karma, since the point of reincarnation is to experience the fruits of our karma. This rests on realizing the true nature of ourselves, which is our soul, atman. At this point, all the lessons from our previous lives have been learned and all karma has been fulfilled, so there is no longer a need to return again.

This is similar to other spiritual traditions, where someone must gain truth about a higher reality (beyond the world they live in) and their own nature in order to escape from the burdens of the world to go to a realm of peace. It's interesting just how many different religions and philosophies have similar ideas about reincarnation, which might not be a coincidence. There are also many accounts of people who are connected to past lives, something sort of like a fluke, since we're not "supposed to" remember previous lives. You can read about how this relates to science in a neat book called The Soul Genome.

See what me and other Muse it Up authors say about the process of writing novels:

http://museituppublishing.blogspot.ca/2014/09/sunday-musings-september-21-2014.html

Science is philosophy, I'd like to argue. The original term for science, "natural philosophy", was much more apt to describe what it is. But what is "natural philosophy"?

Natural philosophy never really "started", for the natural desire for humans to inquire and understand the world is intrinsic to our nature, and so in a sense we have always been natural philosophers. Aristotle, however, contributed greatly to our understanding of nature through his observations and philosophy. To Aristotle, natural philosophy was concerned with analyzing the causes behind natural phenomena, such as: why does the sun rise each day? Why does a plant grow from a seed?

Natural philosophy never really "started", for the natural desire for humans to inquire and understand the world is intrinsic to our nature, and so in a sense we have always been natural philosophers. Aristotle, however, contributed greatly to our understanding of nature through his observations and philosophy. To Aristotle, natural philosophy was concerned with analyzing the causes behind natural phenomena, such as: why does the sun rise each day? Why does a plant grow from a seed?

In the Medieval world, Aristotle's work was rediscovered in Europe from where it was preserved by the Islamic world, and it was incorporated into Medieval theology. Natural philosophy and theology became the vehicles to understand the world, and together, they were used to describe the world in terms of purposes and connections to higher powers. Everyone learned Aristotelian philosophy, and Aristotelian scholasticism dominated natural philosophy, and indeed, became synonymous with it, until late in the seventeenth century.

During the seventeenth century, natural philosophy was transformed by the Scientific Revolution. Advances in mathematics, experimentation, and technology greatly changed the Medieval worldview. The natural philosophy of the 17th century started to resemble what we now call "science", and was largely spurred by Descartes and Francis Bacon. They focused on extracting truth about nature by theoretical (mathematics and logic) and experimental (observations, telescopes, etc.) means in order to describe a mechanical universe without direct divine intervention. However, they certainly had their own theologies incorporated into their philosophies, though these usually were not theological explanations for natural phenomena.

Natural philosophy continued its spurt of development up to the present (and, of course, it's still going on), evolving our picture of the universe by the works of people such as Newton, Copernicus, Galileo, Darwin, Faraday, Einstein, Bohr, etc.

Although the conception of natural philosophers has changed over the course of the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and especially in the seventeenth century, the pursuit of knowledge about the physical world was not separate to philosophy, but was indeed a kind of philosophy. Natural philosophy was not so strictly classified into disciplines like Genetics, Neuroscience, or Mathematics (many of which our nineteenth century predecessors labelled), but all disciplines were seen in a more united sense than they are now. There is certainly overlap now, but the general division seen in schools does not help to portray the underlying unity between the areas of science. And indeed, it does nothing to show the unity of science with philosophy, both of which might as well be living on different planets. But philosophy is a study of the fundamental nature of the world, of knowledge, and of all of reality. Above all, it is a method of inquiry, of using rational thinking to come to a better understanding of one's self and the world. It is a love of wisdom, as its name in Greek implies. Where science fits into this is that science is a kind of philosophy, namely the philosophy of the natural world, as opposed to ethics or logic (though logic is obviously used as a tool in science).

You can read another article about this topic here.

Tweet

I recently finished a book about the philosophy of the Druids, the best one I've read so far, and this quote is about one of the ideas the Druids had that is in common with many other ancient religions and philosophies.

I recently finished a book about the philosophy of the Druids, the best one I've read so far, and this quote is about one of the ideas the Druids had that is in common with many other ancient religions and philosophies.

From Sir John Daniel's The Philosophy of Ancient Britain (1926):

"The Science of Correspondences is therefore the science by which we perceive principles operating in the spiritual world, and by which we trace those same principles in the order of their progression into their types in nature, and thus prove by strict analysis the truth of our perception. It unfolds the correspondence between things spiritual and natural, between every object in the spiritual world, between God and His Church, and between the spirit and the letter of His Word."

The Science of Correspondences (SOC, I'll call it for short), was first written about by Emanuel Swedenborg, though it was known to the ancients, such as the Druids, centuries before. The basic idea is that everything in the world, from plants to humans to stars and galaxies, corresponds to higher spiritual principles. This gives them their order, the laws by which they unfold. It's sort of the same idea as Plato's forms, the eternal, unchanging concepts that things in the physical world partake in, like a plant participating in the perfect form of "plantness", though it is never as perfect as the spiritual form.

Just about all of the Bible was written by means of correspondences, such as, as Swedenborg pointed out, the sacrifices, offerings, clothing, and all those little details about buildings and things that don't seem important, though convey a secret formula that can be read by people who understand the encoded SOC.

The SOC can aide us in understanding the foundations of our scientific knowledge as well, as John Daniel points out, saying that the scientist, "having done his utmost...to reach a solution to the riddle of the universe...is faced with a hiatus he cannot bridge, an infinity he cannot fathom." This sounds similar to what is facing physics right now (even though this was written in the 1920s), with the attempts of particle physicists to probe deeper and deeper into the nature of matter and the structure of the universe. The SOC can aide us in understanding the uses of things and their cause and effect. This is not to put a divine purpose into every little thing in the world, but to see greater patterns in the evolution of the world and the universe at large. It is "the Science of Sciences", what I think is a more metaphysical kind of philosophy of science. It connects the workings of the world with more basic principles, and as John Daniel says, "as the natural world is one of the effects whose causes are in the spiritual world, and whose ends are in the Divine, it is impossible to understand the meaning of one link without having regard to the complete chain."

I think it is important to have more philosophy in sciences, especially physics dealing with the very small and very large, and the SOC is certainly a way to do this. Whether it will be able to 'bridge our hiatus', I don't know, but by uniting the spiritual aspect of the world with the physical (a very Aizian idea, if you've read my novel Aizai the Forgotten), we can certainly gain a better understanding of the universe. Especially with physics theories about the multiverse, extra dimensions, the universe as being a mathematical structure, and other such things, what if what they were describing is a fuller spiritual world? This could correspond to philosophies such as Kabbalism or Neoplatonism. For example, in Neoplatonism, each level of existence, "hypostases", is a reflection (or dispersion would be more fitting) of the one above it, and so the lower worlds are a reflection of the higher, creating a link between them. And so we see the well-known phrase again: "As above, so below".

I think it is important to have more philosophy in sciences, especially physics dealing with the very small and very large, and the SOC is certainly a way to do this. Whether it will be able to 'bridge our hiatus', I don't know, but by uniting the spiritual aspect of the world with the physical (a very Aizian idea, if you've read my novel Aizai the Forgotten), we can certainly gain a better understanding of the universe. Especially with physics theories about the multiverse, extra dimensions, the universe as being a mathematical structure, and other such things, what if what they were describing is a fuller spiritual world? This could correspond to philosophies such as Kabbalism or Neoplatonism. For example, in Neoplatonism, each level of existence, "hypostases", is a reflection (or dispersion would be more fitting) of the one above it, and so the lower worlds are a reflection of the higher, creating a link between them. And so we see the well-known phrase again: "As above, so below".

If our physical world is derived from a higher spiritual world, we will indeed reach a limit in our understanding of the physical universe as John Daniel pointed out, even if there are higher physical dimensions and other worlds, because the laws that govern our world derive from laws that encompass a higher level of reality. So we have to go a step above, and science, since it deals with understanding the physical world, can't get there without something else. Mathematics might well connect our world to others, and we can already see this with string theory, higher dimensions, and other such theories.

It seems like the ancients, with their SOC, knew something which we would do well to uncover if we actually want to understand the universe we live in, and to understand ourselves.